ISSUE 20

GURULEEN KAHLO

The world felt large. Every building looming. Every person a threat. It had been a week since I had last left the house. I had spent that time curled up in my bed, phone in hand, as I endlessly scrolled through stories of men with bricks, chainsaws and bloodied fists. The target was every non-white person their mob came across.

I hadn’t wanted to leave the house that day, but was left with no choice. I was working on a project that needed me to explore an archive from one of three options. I had chosen a museum. When I chose it I had no idea that they were going to temporarily close for most of the summer. So there I was, walking down the never-ending road on the last day the archive was available to me.

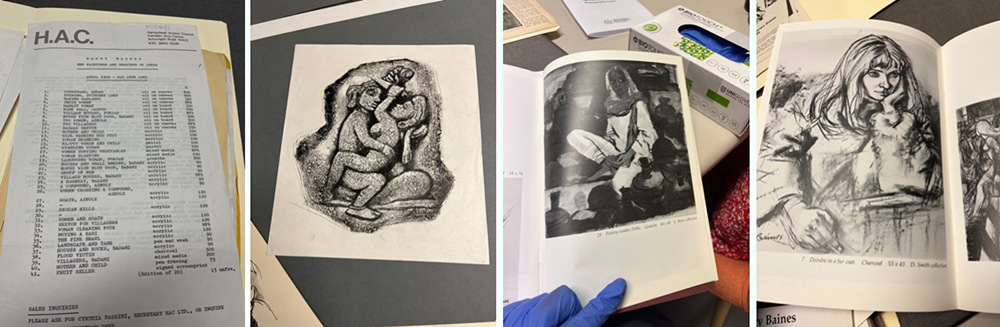

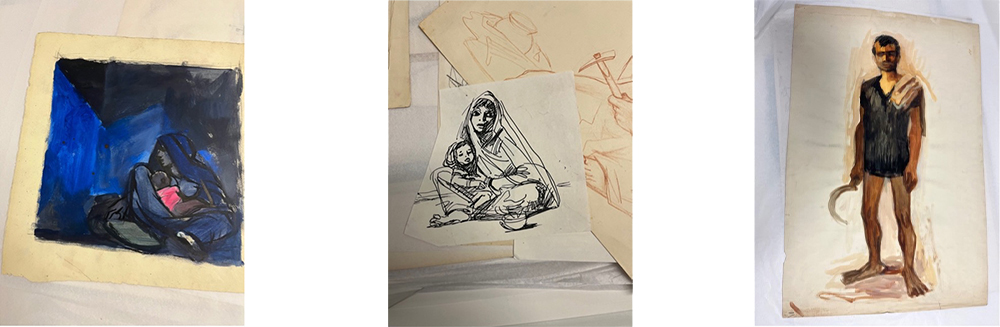

By the time I got there I was breathless and coated in a fine film of sweat. I was presented with the folders I had requested prior to my visit. When I had typed India into the archive’s search engine I was greeted by a series of codes, each accompanied by a short bio. The name Harry Baines came up repeatedly. I took a risk and asked for several of his files.

As I flicked through the first, it didn’t seem like the risk had paid off. I felt like all the staff were staring and wondering what was wrong with me. Sketch after sketch of sex positions, women twisting and turning. My heart began to pound in my chest. It was the last day and I had asked to see reams of this?

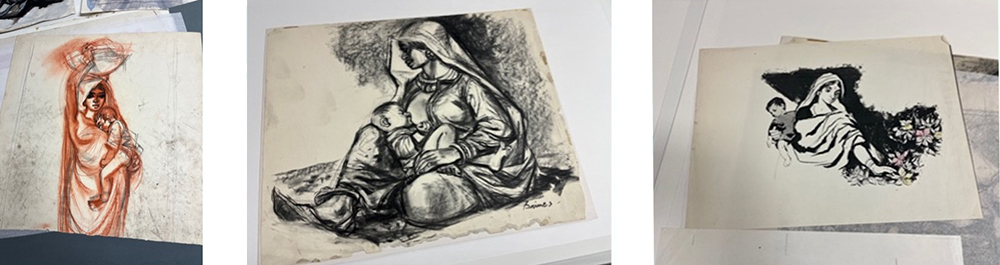

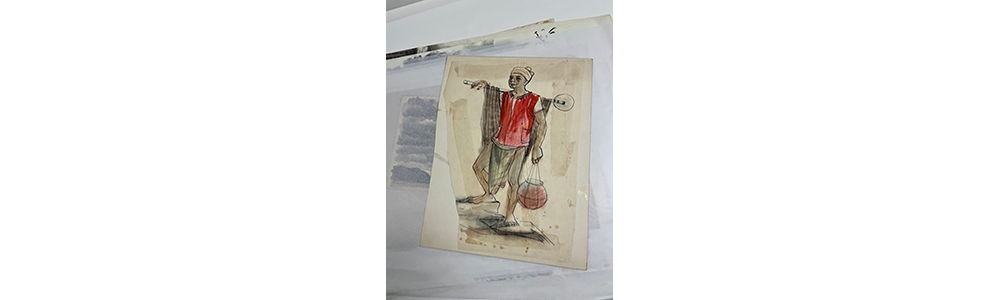

The relief I felt when I opened the second folder was indescribable. I wasn’t thinking critically at first, I was just happy to see drawings of people dressed and living their lives. Women on the backs of scootys, men farming, women sleeping with their small children. Women sleeping with their small children.

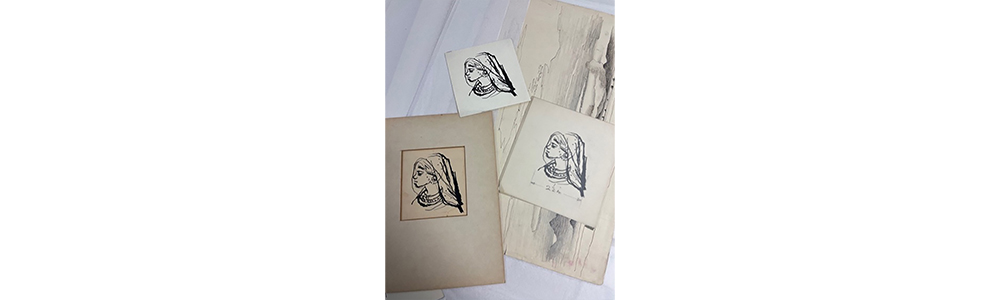

Why are there so many drawings of women sleeping with their children? A baby nursing at its mothers breast. A girl cradling a baby. So many women in vulnerable situations. It almost felt worse than the first file. I had so many questions. How did he get into their homes? Did he tell them what he was doing? Did he ask them in Punjabi? Hindi? Malayalam? Or did he consider his white skin an access all areas pass?

The third file didn’t make things better. Littered throughout were receipts of donations from sales. Money sent to churches in Dover. Communities in Cornwall. Nothing for the villages and cities in India.

Exhibition flyers showed canvases of white women. These women were straight backed, elegantly dressed. The portraits were posed, the women aware of the man with sketching pad. They were also named. Harry Baines had clearly asked them for permission.

I left feeling worse than when I entered. How did he watch the Indian girls? Did he sneer? Did he show his friends and buyers how “they” live?

Weeks later I sat down to write my first draft. The questions played on a loop. All I felt was rage. I began to write, pouring out my hatred, my fury at centuries of oppression. It was only when I read it back that I realised.

I am full of biases.

What if he did ask in Hindi, or Punjabi or Malayam? What if he did donate to villages and cities?

SKETCHES

The Dawn

The woman rises before the sun. She dips a small pot into the bucket of water collected from the well the day before. It traces her soft stomach and caresses her sides. Her dark hair coils down her back, stretching past her thighs. A deep breath. A pause. A moment of peace.

The baby starts wailing.

Her body is dripping as she hurriedly drapes her sari. First around her waist, then across her chest before finally pulling it over her hair. Her wet feet leave prints on the clay floor. She pulls her child to her chest. The baby feeds. Its grip doesn’t loosen, clinging to her when she lowers herself into a squat. She works away at the tawa. The wet patches on her sari slowly fade.

Light bursts through the cracks of the blinds. Eventually her husband has no choice but to join them. He brings with him a squirming toddler. The pair take their place beside her as she hands them loaded thaalis. Minutes pass. The sound of chewing pauses momentarily when he hands her the thaali for a reload. The chewing recommences. Only after they have both eaten and walked away does she take her portion. It’s a fraction of what they had. It has long gone cold. She takes her toddler’s half-eaten roti. It’s easier than making a fresh one. And yet despite all this she finally relaxes, knowing they have had their fill.

Wanderer

Strands of colour have carefully been weaved into the heavy braid that traces her spine. You wonder if it weighs down her small head.

Her salwar kameez is almost as bright as her hair. She sports blue on top and pink at the bottom. Her bare feet are cracked and calloused.

She stands perfectly still in the middle of the heaving market. People pass by her so quickly that for a second she is surrounded by shadows.

It’s hard to figure out just how long she’s been there. You start trying to count the minutes. She catches the eye of someone across a stall. You don’t see who. The small girl takes off, leaping over rocks and weaving through people. It feels like an act of defiance. As if she heard you trying to figure her out.

You blink. The traces of the little wanderer are gone.

Scooty

She is preparing the atta when she hears an unfamiliar beep outside the door. She hears the noise again. And again. It’s almost incessant. There’s a small pause between beeps, during which the still not quite familiar voice of her husband rings out. It beckons her outside.

Her mother-in-law is seated on the manja. She looks up at her dutifully, silently asking for permission. The woman tuts sternly “Abhee-abhee shaadee huee hai iseelie”. This is not an answer the woman thinks, still staring upwards in hope. Her mother-in-law eventually gives her a curt nod.

The girl opens the door to find her husband straddling a new scooty. Her intricately patterned hand jumps to her mouth before she can stop herself, her red banga rattling against each other. He gives her a toothy grin as he says “Chalo jaan”. She runs a few paces towards him, before feeling her mother-in-law’s eyes bore into her back. She restrains herself to a walk. Each step feels like an age. By the time she reaches the scooty she is close to bursting. Her mother-in-law is still watching and won’t approve of her sitting “like a man”. She barely manages to remember to sit sideways. She leans forward, mouth to her husband’s ear. Her “Dhanyavaad” is drowned out as the key turns in the ignition.

She wraps her dupatta over mouth and nose, and for a second she feels like a daku. They race down the paths. The sharp air yanks chunks of hair out of her carefully manicured plait. She contemplates her mother-in-laws reaction, before the wind makes her forget entirely. She finds herself pulling out the bottom of the braid. It only takes seconds for the whole thing to unfurl. It flies wildly. The wind embraces it, running its fingers through, the way her mother did not too long ago.

The Day

He’s walking down the path he knows best when he sees his neighbour. The man informs him of another suicide. He found the body, swinging limply from a tree. The village is slowly losing its men. They didn’t need him to leave a note. They knew what it was. The debt. The poor yields. Either way, it all lead back to money. He comforts the man before he journies on, trying to dismiss what he heard. He pictures himself arriving at a bountiful farm, lush with crops.

By the time he arrives, the heat is unbearable. There are no trees to take shade under, their branches have long been bare. The land is flat. Dust swirls each time he lifts his feet. He starts to picture the body swaying, the birds feeding on the corpse. His heart starts to race, as a flood of desperation knocks him down to all fours. He claws at the ground, to find something, just something sprouting. Fragments of rock embed themselves into his nails. They start to crack and bleed. The ground guzzles up his offering. He keeps at his attack. And yet the earth gives him nothing back.

He returns home at the usual time. His wife is already suspicious. She has spent the season reminding him that he matters more to her than the money. That may have once been true, but what she needs now is one less mouth to feed. It has been months. They can’t sustain this. His plans are all but set in stone. Until he hears the feet pattering towards him.

“Pappa!” The small voice squeals. “Pappa!”. The man scoops the child into his arms. He holds him snug to his chest as he buries his face into its warm hair and promises himself he will try again tomorrow.

Scrap Paper

An advert is listed in today’s paper.

Wanted, Sikh/Hindu match for Sikh boy, 28, Master Engineering America, drawing dollars 1400 per month. Early marriage. No bars. Box 3847 – CA. Hindustan Times, New Dehli-1.

For a moment the reader considers their niece. She has also been studying to go abroad. Her English isn’t as strong as their daughter’s, but she’s a hard worker. She’ll get there. And even if she doesn’t, she’s got some good work ethic. The age would suit too. She’s 25, or near about, the reader thinks. They start to rip out that section of the paper as a reminder to mention this match to their sister, when they remember their niece doesn’t want to go to America. For now, she has her heart set on England. That’s where her sister’s gone. And where most of the rest of them want to go.

Ah well, the reader thinks, as they get up and leave the bustling dhaba. They leave the paper next to their empty glass of chai. Someone else can get a read of that, maybe the boy will find a match, they think, and if not they can always just use it as scrap paper.

Patang

She hikes up the stone steps, the wicker basket at her waist leaden with wet clothes. At the end of her climb she is greeted by the open sky. A bright blue, with a smattering of cotton white clouds. She cranes her neck looking up and finds herself at the summit of the Himalayas. Alone at the top of the world, she takes a breath of the cleanest air. Her dhadi ji is so proud of her.

Until a fluorescent pink patang streaks across her view. It pulls her back to the flat rooftop with its wet clothes and laundry line. A purple follows, then a red, a yellow, a green, an orange. They all chase after the other. She can’t help but sit and watch as the sky lights up. Her peace is momentary. A young boy’s delighted shriek cuts through the cacophony as the pink patang flutters to the ground. The first kill of the game.

It lies there, bold and unashamed. Her heart sinks at the thought of it being worn down by passers by, the colour fading, its structure eroding. The steps are nothing to her now. She rushes down and back up, patang held carefully in her arms. By the time she returns, only two remain.

As she ties the string on her new friend, ready to enter the final, she smiles to herself. Why would she need to climb a mountain when she can fly right here?

Gaihne

People hear her before they see her. She is the sun. Eyes take time to adjust. Her paile ring with each step.

Light radiates from her skin, from her gold. The word adorn was made for her.

She must be descended from royalty. Her strong brow gives way to a hooked nose, that leads to her full lips that sit above her gentle chin. She flows like a river, yet her back is as rigid as a board.

She doesn’t speak enough for anyone to find much out. Most of the people here struggle to remember her real name. They’re too used to calling her gaihne.

The Night

The moon watches over her as she sits outside and prays with her back against the wall, her baby in her arms. She prays. She prays to Allah, to Waheguru to Dhanvantari, to every god she can name until she forgets which one she was raised to believe in.

Three days ago, they managed to pull together enough to see the doctor. He told the family to give up. He told them that the fever is too strong. They are still young and fertile. She doesn’t want to try again. She wants this baby. This baby who doesn’t cry. This baby who can only fall asleep with its whole hand curled around one of her fingers. This baby who isn’t even old enough to be named.

Everyone in the house has told her to listen to the doctor. They cannot stop her feeding the baby. She cannot stop nature from taking its course. They are all starting to suffer. They are the victims of her rage and depression. It is not worth it for such a lost cause. Still, she does not listen.

Her tears wash her child’s face. They sit together in the black and blue of the night.