ISSUE 18

Fahad Al-Amoudi

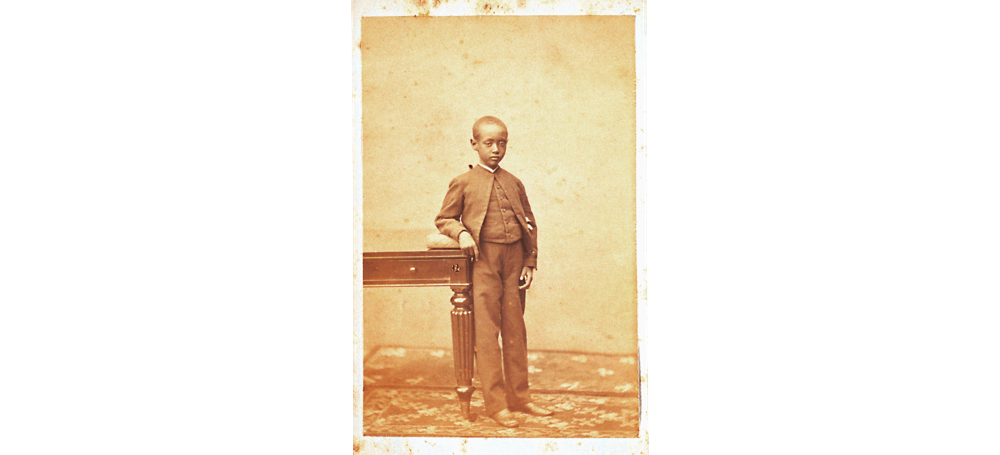

In 1868, the British Government sent a military expedition force to Ethiopia to retrieve envoys, who had been imprisoned by Emperor Tewodros II after a breakdown in diplomatic communication. At the Battle of Maqdala, the Ethiopians lost and the Emperor killed himself. The British Expedition force, containing a few private collectors and one British Museum curator, looted the fort of Maqdala and surrounding settlements, setting them on fire. Soldiers stripped the late Emperor of his clothes and took locks of his hair. To this day the remains of Tewodros and many of the stolen objects remain in museum and archive institutions across the UK, including the British Museum, the V&A, Windsor Castle and the National Army Museum. A few weeks after the battle, the Empress Tiruwerk died of an unnamed illness. General Napier and Captain Speedy decided to take her only son back to the UK against her dying wishes, where he lived mostly in Leeds until he died of pleurisy at the age of eighteen. The prince’s name was Alemayehu.

These are fictional letters he wrote to his grandmother.

The Letters of Prince Alemayehu (Son of

Emperor Tewodros and Empress Tiruwerk);

album; museum no. 372.847; 1871-1879;

[incomplete– see Appendix for curator’s notes and additional information on the text]

i. Cicada

I can’t see water but I can taste salt in the wind. It is morning. There is only one season here and it is the rainy one. Clouds rub against each other like cicadas. You can even see where they meet and run your finger along the edge of their precipice. The light is dull. It falls through the gap like syrup. It is nothing like the hills back home. Where your breath drops over the ledge. I miss that feeling of your spine filing against the sun. When you are so high that your gut is a masenqo string. This island is one grain of rock salt slowly dissolving in the water. Ayat, everything is bitter. Sea foams on the lips of the cliff face bending upwards in baby elephant tusks. Every day I wait for the water to claim us. People here talk like they are drowning with a swell in their throats. Talk of more rain. Won’t you come visit? Even if I have joined the underwater kingdom, where seagrass braids my hair and the current cuts into my ribs like gills of a fish. Captain Speedy says he decides if we have visitors but assures me that I am allowed to send you these letters. I hope they reach you in good health. I miss you, ayat.

iii. Balalebo

Do you remember the rhyme the chroniclers used to recite about my father? The one about jewellery? We used to laugh at that one. They composed it on the campaign at Injibara? One of father’s great victories. They would sing about how he cut down the knees of that town; how the people laid their necks at his feet like ribbons. That day the sun found every blade smiling. The last prisoner to die clutched at the gash across his throat, helpless to stop his blood turning into cinnabar gemstones. The bodies were tossed aside like a split pearl string.

All I have left are flashes of memories. Some bleed into one another like the features of neighbouring cities. My language is in a ravine between the curb and the road, crowned by vultures. Each word unpicked down to the marrow. Unrecognisable. I do not remember being black. All I know is the mountain adder hiding among the coffee plants like stonefruit. Mother’s hands wrapped in white cloth, blotting out the sun as armies torched the fort. My body is a copper bath filled to the battlements with scalding water.

These days, I am taken from studio to studio to be photographed. It’s always the same shot. Crossed legged at Captain Speedy’s feet. Wrapped in a cape. Fake necklace of lion’s teeth laid on my shoulders. I am told to smile. I smile. Today I saw a picture on the mantlepiece. Nestled underneath a wall of prizes–a giraffe’s head, a tuft of lion’s mane, crossed ceremonial spears–I saw a boy in a picture, dark of complexion, a dull muslin, his short woollen hair in a widow’s peak, orphaned by the thing around his neck. That was when I remembered the rhyme,

‘There are many decorations in the house of the Negus

he has made all the women owners of necklaces.’

vi. [Return to Sender]

Sometimes, I see your bent shape in metalwork by the shipyard;

your smile in the glow of hot iron, curved to the handle of your cane;

ivory but with a silt of tooth decay rounding out the edges.

You roll into view like fog off the dock,

your body wet and doughy, your chestnut eyes poked into your face

clumsily, as if by a child’s fingers, the rolls of skin like damp rags.

I wish you would tell me where you have gone; in what plane

do you live now? You have not written to me in all the years

I have lived in this city. I am lonely as the ibex, kicking paving

stones in the street, the taste of blood and backwash swilling

my throat, seeing shapes in the low-lying cloud, seeing you

Grandma, disappear on a wingspan of lungs heaving against the gloom.

vii. Mistranslations

If a priest hands you a noose

and says, make of it what you will,

do you braid a rein for the ox,

plough the field till the sun fells?

Do you make an anklet for your lover?

Lanterns swinging in her eyes, and the bard,

who sings the old fable of wedded hands

by shallow graves in church yards.

Outside my window, cherry blossoms

bear no fruit, the night conceals the brave,

and all the boys who look like me

are shadows in a far-off cave.

Time’s a jade river, a clouded snake

wrapped around my waist in a belt.

Who else bears the mark of Cain,

haunted by memories of a future self?

A language of idioms, I am heard in all

ways but the one I need. I move through

this earth like coins in a ship’s hull,

a tide sloshing through a boxer’s knees.

My end is not the hangman’s crucifix,

the trinket holstered to his hip, I am

an echo of home, a pastel dawn

in the land that begins with the sun’s lilt.