ISSUE 20

INTRO

In the second version of Writing the Archive, we followed the steps of Fahad, Lydia and Prerana. The brief was similar: for a group of writers of colour to respond to an archive. Where the first team had worked with the British Museum only to be ignored and locked out of the institution, this time, we were invited in. Our project was hosted by Manchester Poetry Library, and we explored materials from the North West Film Archive and Manchester Metropolitan University’s Special Collections.

Working with an archive is complex. And unwieldy. And overdone. We can’t count on our fingers the number of recent exhibitions that have used “archive” in the title, as if the word holds a special key to unlocking legitimacy, political urgency, or extra funding. In fact, in 2021, the American Historical Association published an article called “Please Stop Calling Things Archives”, referencing the over-casual use of the word. Librarians, archivists and curators are apparently very upset to see their “professional terminology co-opted in imprecise ways.”

We suppose you could say that what we’ve done here is imprecise. If you’re a librarian you might be upset. This isn’t recovery work and we haven’t rescued anyone from the archives. It’s work that pulls at the seams and tests the archive’s edges, or in the words (and visual poems) of Kayleigh, we’ve thrown “all the letters in a frying pan” to “crisp them up.”

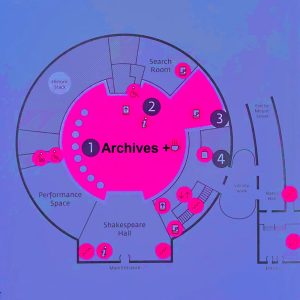

Sometimes we’ve torn up the physical matter of a space. Tayiba repurposed advertising material from leaflets at Manchester Central Library to create a series of visual collages. The leaflets invited readers to Share Their Central Memories. But memories are a bit like archives. They’re hazy. They blur into dreams, or lies, or national mythologies. Sometimes they look like abstraction paintings, like an Etel Adnan landscape with a wobbly sun, or the circular blueprint of Manchester Central Library, hovering in the middle of a line that won’t settle.

*

We had an easier ride than Fahad, Lydia and Prerana. We had their workshop and their poems to guide us when we felt unsure of where to start. We had Ruth and Martin and Steve supporting us throughout. We even got a tour of the North West Film Archive, where, in the basement of Central Library we followed reels of film deeper and deeper, moving from one room to the next, each colder than the last. Coloured film was stored further in (it needs to be kept colder than black and white) which felt weirdly poetic. We were surrounded by newsreels, adverts, footage of local protests, football matches, street parties, home movies. All of the films were just there, captured and wound tightly into canisters. It was strange and brilliant and we think you should all go visit at some point.

Part of the collection were a series of Calling Blighty films – video messages by British servicemen stationed in ‘The Far East’, sent home to their friends and families. I worked with a film that featured servicemen in Malaysia sending Christmas messages home to the North West. Their black and white bodies come up to the camera as they fidget between awkward grins. “I’m afraid you’ve got all the advantage cause you can see me and I’ve got no chance whatsoever.” The sense of being looked at – unable to look back, felt familiar. I, too, was reaching for something preserved, only to find a conversation I had arrived too late to enter.

Still, not everything went to plan. In July, just as we were deep in our research, we got an email saying that the University Special Collections would be closing for most of the summer. Guruleen managed to get in on the final day they were open, chasing a name that cropped up in a search involving India. We won’t spoil what was found – you’ll see it in the work – but we will say: the archive rarely surprises. Or maybe it surprises in the same way, over and over. The same patterns and omissions. The same neatly labelled boxes that quietly tell you what not to look for.

*

Sadiya Hartman writes that the archive is “an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.” Her method to strain against a collection that is loaded with invented evidence and violence. She chooses “critical fabulation” – a method of straining against, in order to explore the personal and subjunctive. You can’t always rewrite history.

In the archives you’re left to deal with the edges of something. Except the edges are always trickier to trace than you think. “That’s the problem with circular buildings,” Tayiba writes, “You can never quite tell if they have their back to you or if they’re looking you in the face.”

From 30 July to 5 August 2024, far-right anti-immigration protests and riots occurred across the UK, targeting hotels housing asylum seekers. They echoed language that has circulated for decades: Britain under threat, the outside as danger. One government caves and another replaces it – warning, as heard in recent remarks, of an island of strangers. The same way, over and over. The same patterns and omissions. This all too, will be the archive. We watch, fingers scrolling through our phones at the genocide that is happening in Gaza as organisations and nations watch on, quietly erasing.

*

In September 2024, we held a workshop based around our work for the Writing Squad, Writing the Archive 2. At the start of the session we asked writers to write down words that they associated with archives. We built a wordbank together. The most common entry was “history”, followed by “past”, “books”, “catalogue.” Other fantastic words emerged too, like “non-capitalist rhythm”, “80s gay magazines”, “slippery” and “weeding”. We invited the group to write their own personal archive through objects and images – comprising things that don’t always cleanly fit into structures.

With imprecision, in the right way, comes care and disorder. An abandoning of terms used to inhibit, gatekeep and tidy. We want more feeling, less system. By that we mean, not everything here fits the strict definitions of what an archive is. Gathering without categorising. Holding without fixing. These are some of our writings from the project. If you’re a librarian and you’re upset, or the opposite of upset, we’d love to know.

Best,

Chloe, Tayiba, Kayleigh and Guruleen.

This iteration of Writing the Archive was funded by Manchester Poetry Library and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation.